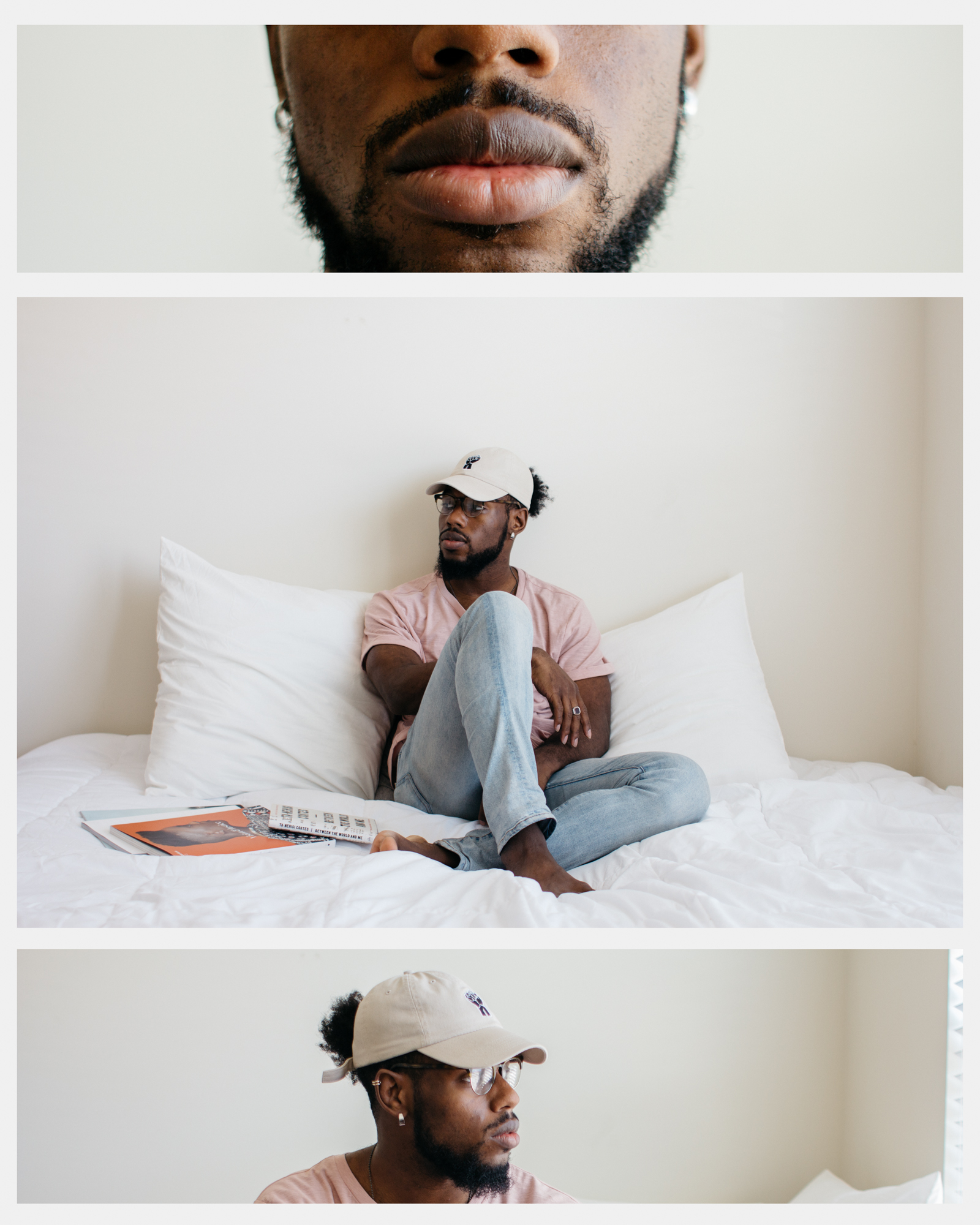

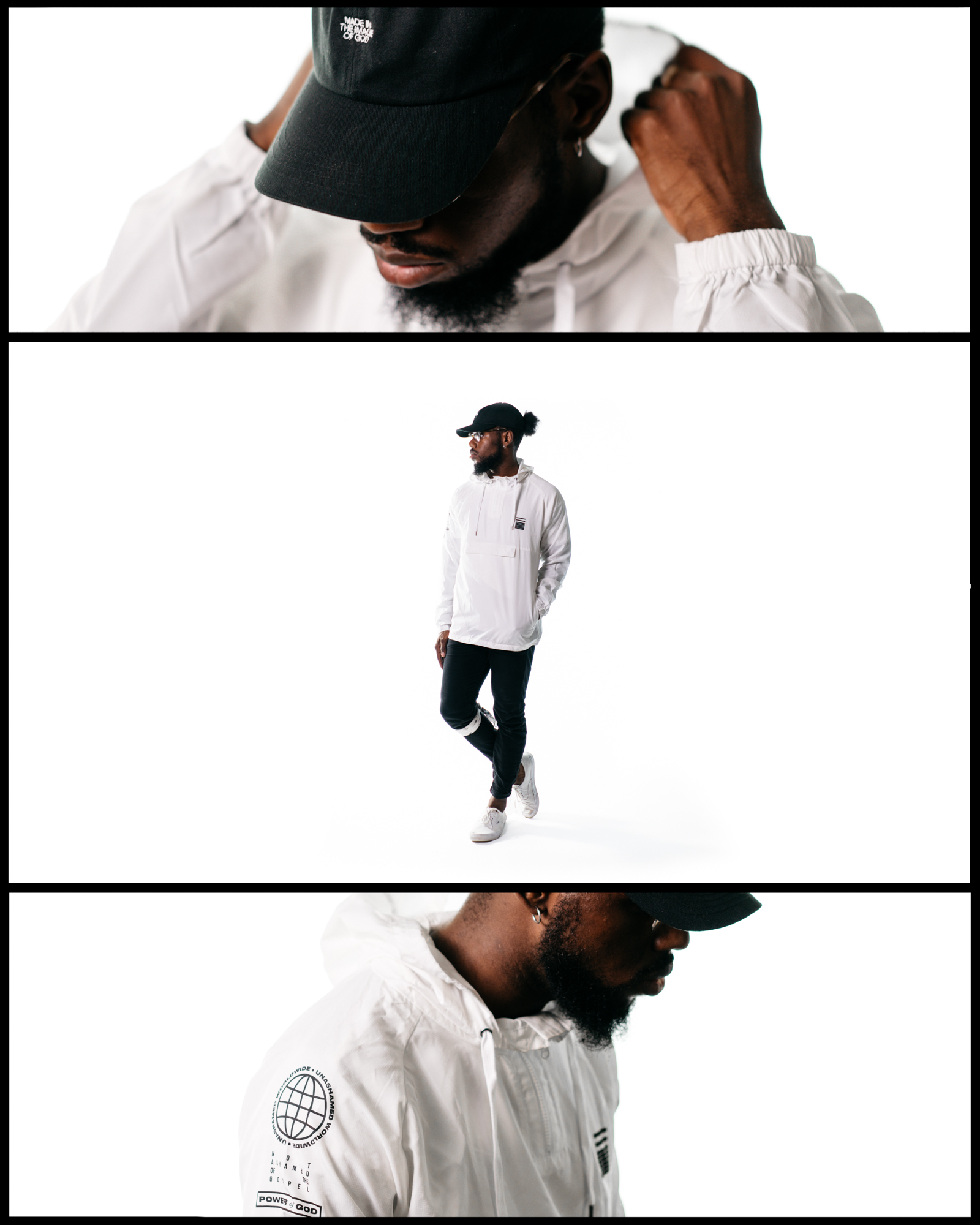

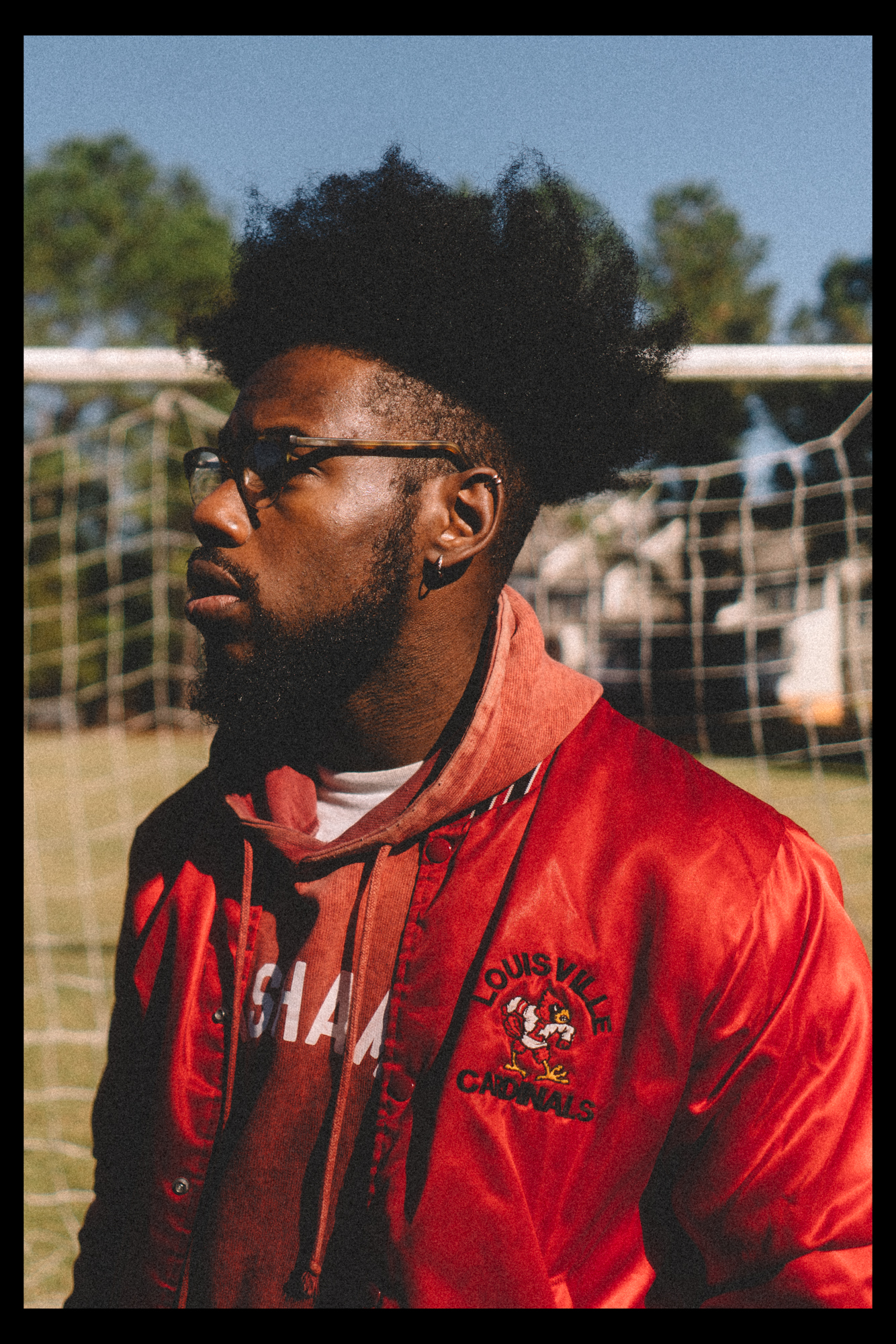

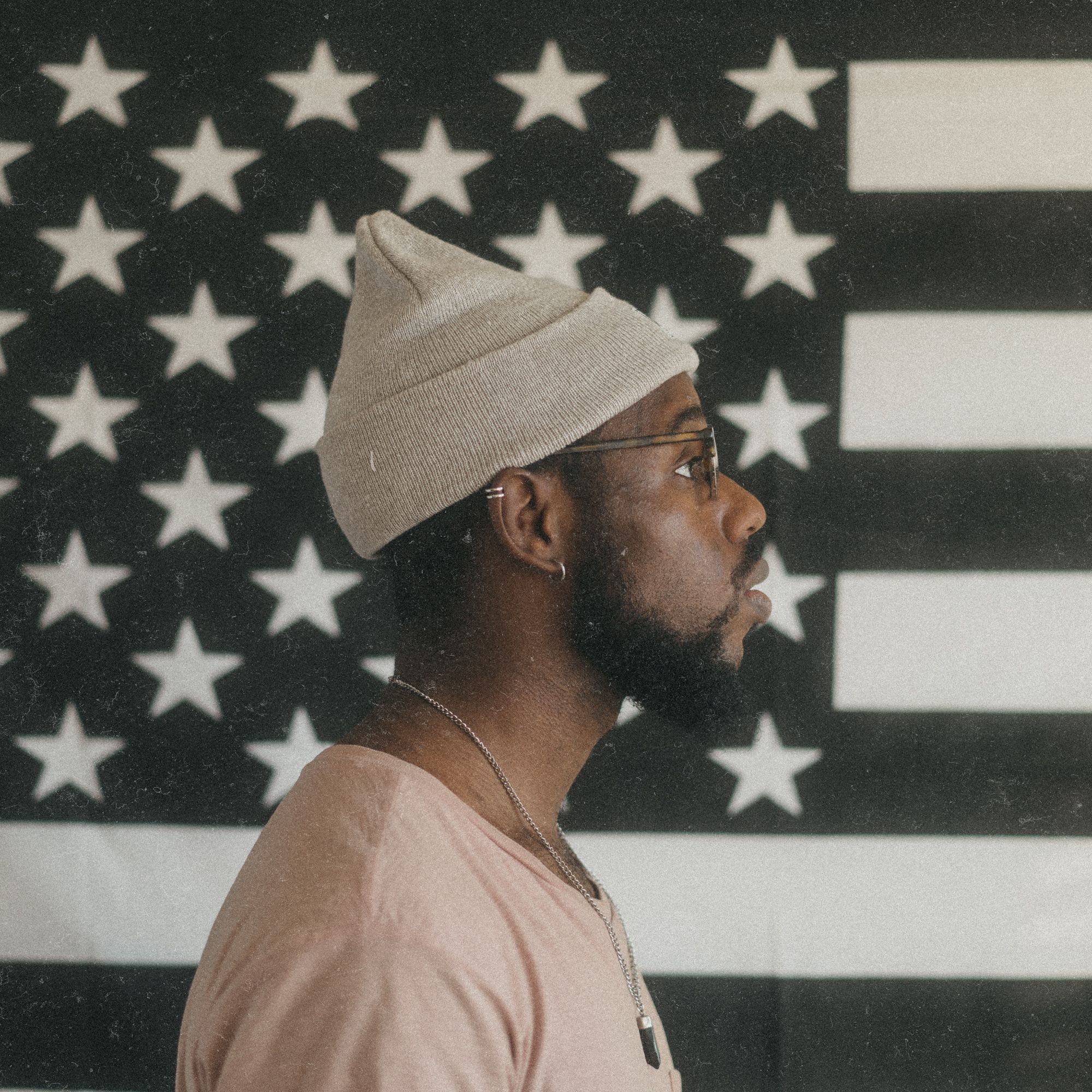

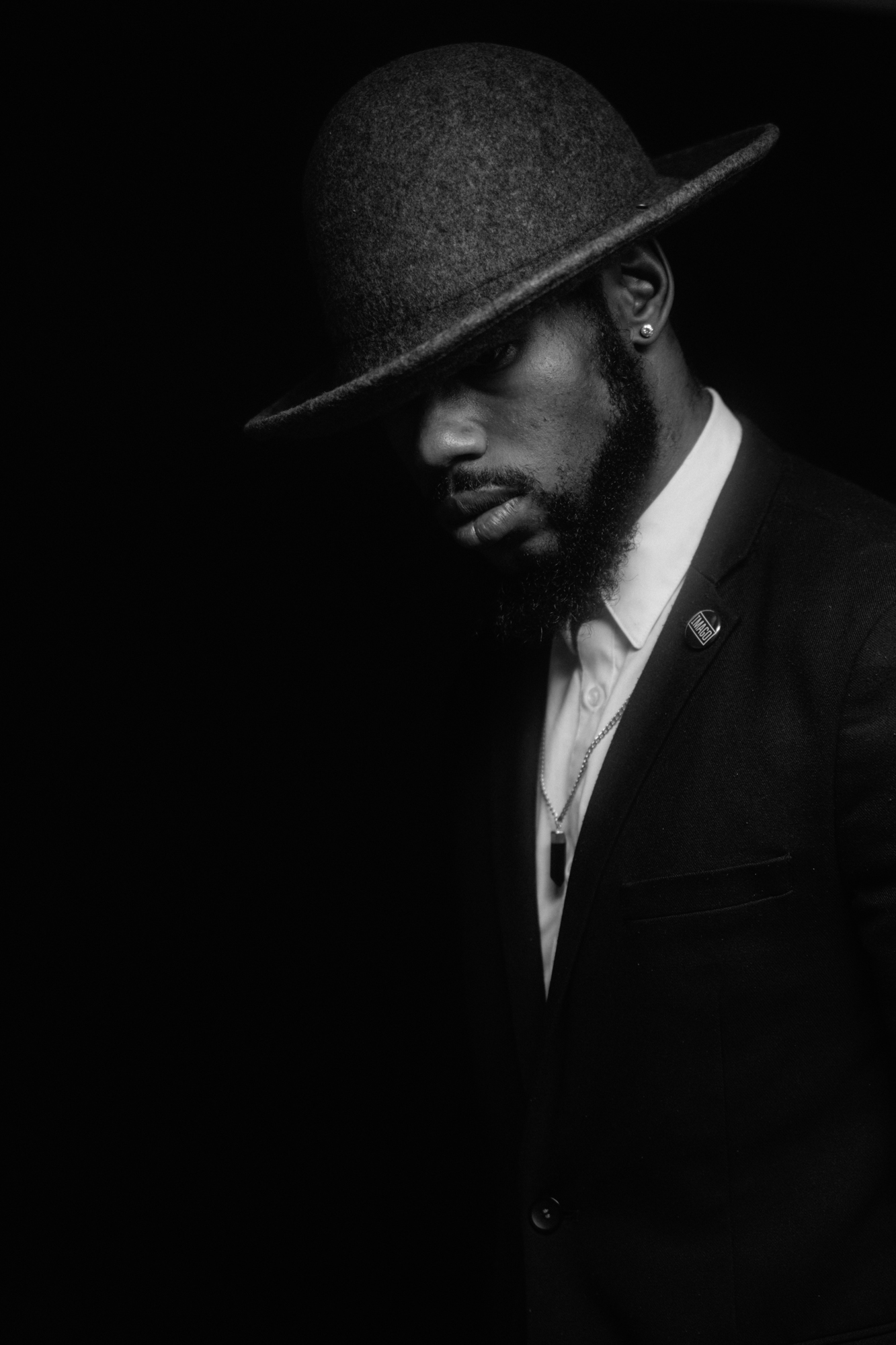

FRESHNESS FRIDAZE

In May 2017, I decided that I wanted to speak into the race conversation consistently through my art, but also in a very personal way that could also empower other peoples of color. I wanted to create a formula that was sustainable, but authentic to who I am and my experiences. From that a project that was initially going to be intended to just focus upon racist or racially insensitive experiences that I have had concerning my physical features as a black man soon grew into a series to focus upon all of the experiences of racism that I could remember. For 53 weeks I dedicated time on my Fridays to photographing a self portrait and pairing that with a caption that detailed a personal experience with racism.

07

At the age of sixteen, I was walking around a store in a mall in Virginia Beach looking at the clothes and shoes. I kept noticing this older lady, who was a sales associate, watching me and acting like she was checking different racks near me, regardless of where I walked in the store. I asked her, “How’s it going?” She was startled and told me she was fine. The following continued, until I started looking at the shoes and she then asked me if I needed help. I told her I was just looking. Even then she just stood there–watching me. I left the store–very aware of what just happened. It wasn’t the first time and it wouldn’t be the last.

10

One day in middle school, I was riding the bus one day and had arrived at the concept of Black Power and the Black Power fist. I remember throwing up my fist and saying, “Black Power.” And there was this boy on the bus sitting in the same area as me who asked for me to do it again. Once again, I raised my fist and said, “Black Power.” He the grabbed my wrist and said, “White Control.” And that was the running joke for a while that year for the white kids on that bus.

11

The summer after I graduated college, I was shopping in a mall in Vegas with my brother, nephew, and little cousin. Our little cousin was heading to college, so we wanted to cop him some new clothes. We were shopping in a store and enjoying our time, talking, laughing, grabbing different things we thought were fire and just having a good time. I was holding all of the clothes and a sales associate walked up to me and asked if she could hold what I had at the front. I thought nothing of it and handed it over and we continued shopping and vibing out. We bought what she put up front and a couple other things then left the store. As we were walking to the next store my brother smiled and asked me, "Yo, did you catch the vibe in there?" I told him, nah. He continued, "They thought we were gonna steal something–that's why they asked to hold that stuff at the front." In that moment, a whole lot made sense.

12

Halloween weekend 2017, I hit up a function with some seminary classmates and just vibe out and have a good time. My homie Kalvin and I decided to dress as Black Panther founders, Bobby Seale and Huey Newton and we pulled it off very well. We were head to toe in all black: the jackets: shirts, pants, shoes, and topped off with berets. All paying homage to the freedom fighters of our past. We had been dancing for a couple hours. Vibing to the rhythms of the beat under flashing lights, with laughter filling the environment. It was a good night. As our night closed, the vibe was split in a moment, as word came to us that a group was asking at the party, “Are they dressed like the black people that kill white people?”

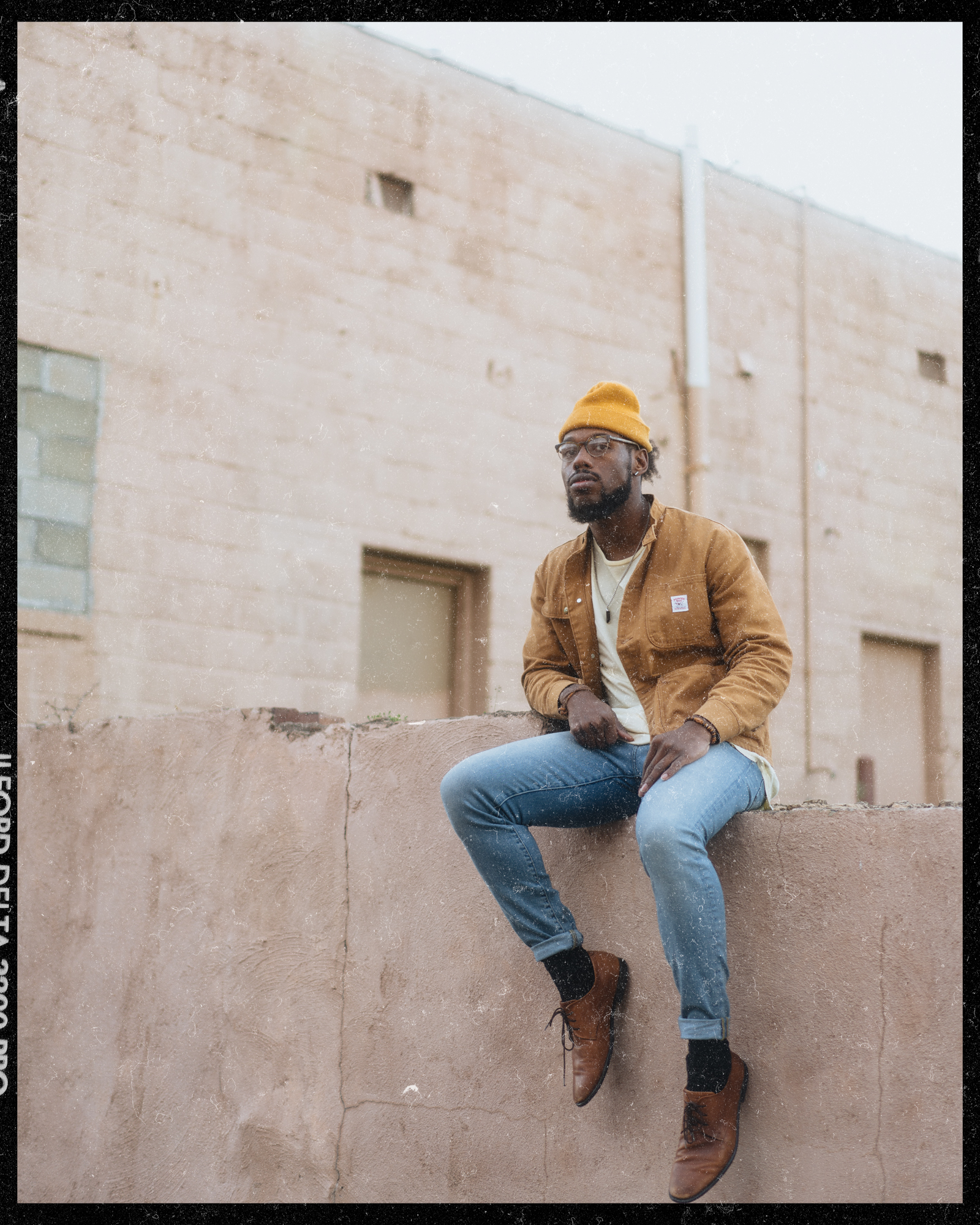

13

It was one of those nights in high school where my friends and I were ready to vibe out into the early hours of the morning playing Marvel vs. Capcom. We were in Walmart grabbing snacks when I strayed from the group to see if there were any good looking fedoras there (don’t judge me). I felt fresh that night. I was rocking a white and red pair of Supra Skytops with a red belt, white skinny jeans, and a white graphic t-shirt. As I stood in the aisle looking through the hats, a middle aged white woman rolled her cart in. She had her head down and, naturally, I looked over to her direction to see who was walking into the aisle. As her head ascend, she saw me. Her eyes widened as she swiftly backed out of the aisle and moved elsewhere in the store.

14

Late fall last of 2017, I was in my first seminary class of the day listening to instructions for the test we were soon taking, while struggling to stay awake. Just as we were about to begin the test, our professor, who was an older white man, looked at me and said, “Your hair is just so interesting. Can I…….,” and without finishing his statement, nor a single word of response or permission from me, he reached out his hand and began touching my hair.

15

A police officer had come to the office of the church I was working at during that time to help with an issue at hand. He had known some of our staff for a long time, so he was sitting at the meeting table telling them, and others around, stories of his life and laughing it up. I was in my supervisor's office next door working, but came out for a moment to hear the story he was telling. It wasn't intriguing to me, so I went back into the other room. As I leaned back in my chair, he said, "Come back, hahaha, come back, come back. He probably thinks I'm gonna shoot him. Black people think all cops are gonna shoot 'em." The silence that proceeded was like daggers.

16

During winter break during my senior year of college, I had a few days off of wrestling and was home in Virginia Beach seeing old friends. One evening, my guy Jon and I decided to do a photo walk in a shopping mall near our old high school. We had been out for about an hour when I had the idea to shoot from one side of the street, while he was on the other side. I planned to shoot with a low enough shutter speed to make the cars blur. He went to the side of the street in front of Kohl’s, as I stood in the grass on the opposite side. As I was shooting, I spotted a police car out of the corner of my eye and as soon as I noticed it, I knew I’d be questioned. As the officer pulled up, full of nerves, I bent down and asked, “How’s it going officer?” He asked “What are you doing out here?” I responded, “Just taking pictures with my friend right there across the street. I’m a college student home for Christmas break and a photo major. It’s been a while since I’ve shot, so I’m just practicing.” He looked a me confused and replied, “You couldn’t find anything better to do?” I responded, “I mean, it’s my major, so I wanted to practice.” The dialogue continued for a few minutes and the officer eventually drove off. Jon crossed over and asked, “What was that all about?”

18

In 2016, I was in a bakery in Tennessee with my best friend, catching up on life, as we normally did there. At some point, a pastor that I knew from the area walked in with his family and they came over to say hi. When they got closer, he asked his daughter if she wanted to come give me a hug. She mistakenly walked towards an older white man instead of me, thinking that’s who he was referring to. At the moment of the mistake, he laughed and said to me, “Well we know she doesn’t see color, so at least she’s on the right track.”

19

It was my senior year of college, and just days before Martin Luther King Jr. Day. I was hanging out with a group of friends on campus and the topic of Martin Luther King Jr. Day came into the conversation. One guy in the group said, “My granddad always use to say, do you know what Monday is? ‘Martin Luther King Day,’ No, it’s James Earl Ray Day, you know, the guy who shot Martin Luther King,” and he laughed.

21

I was a junior in college and the president of a ministry on campus. Late one evening, after our weekly meeting in the dining hall, I was sitting at a table with two close friends at the time, just spending time with one another. We were the only ones in the dining hall. At that time I was deeply troubled by the verdict of the Trayvon Martin case that found George Zimmerman not guilty of his murder. I began voicing that hurt and the frustration with a broken Floridian judicial system that could create such an outcome. As the dim incandescent lights bounced off of the laminated tables, both of those friends began explaining why they believed Trayvon deserved to be shot and why the verdict was just. And I felt deeply–––alone.

22

In fifth grade, I attended Trantwood Elementary, in the suburbs of Virginia Beach. There weren’t many black people in the school and I was the only one in my class. About that time, my brother had me hype off of a Christian Hip-Hop group called Cross Movement. Something about the combination of getting to be like him and what I saw in that sub-culture of Hip-Hop really drew me in. Unfortunately, it was clear that many of my classmates had not been exposed to, not only Hip-Hop culture, but Black culture in general. They’d mock me and make jokes about Hip-Hop , which I was still committed to listening to because I considered my brother to be someone far cooler than the were. One day, the topic of conversation landed on what Hip-Hop clothing styles were like. They challenged me to dress Hip-Hop the next day. I was excited to show the how dope they style was and share a part of myself with my classmates. The following day, I walked in feeling hella fly, rocking baggy blue jeans, an oversized black tee, and a oversized plaid shirt to top it all off. I was welcomes from those same boys to a sea of jokes and laughter. I felt like my culture was fighting for a place that it didn’t have there–and I knew I didn’t belong.

23

As a pre-teen, I was forced to get used to people continuously invading my personal space. I knew if I wore an afro to school, my white classmates would touch my hair relentlessly all day. I would always have a pick ready to correct the form. Black friends of mine who also felt that tension would do the same. We’d always be adamant about people not touching our hair, so they wouldn’t mess it up and we wouldn’t have to pick it out again and I remember us having conversations about it with one another. Yet, it continued. We’d be ignored and they would do as they pleased.

24

I was a senior in college and one of the captains on the wrestling team at a small NCAA Division II school in East Tennessee. It was early in the season and a group of us were chillin’ at a table in the dining hall. After a while, one of the freshman on our team looked at me and asked, “Trevor, why do black people like the name Monica so much?” I responded, “Huh? What are you talking about?” He continued, “Black people always call each other Mo-nicca, hahaha.” I was still confused. “Monica, Mo-nicca, they always call each other Ma––ni–kka, Mah–nigga hahaha.” At that point I realized he was making a joke to say “My nigga” on the sneak. “Ayo, that’s not cool. Chill with that.” He responded, “Hahaha, What? I’m not saying it–all I’m saying is Mah–nikka.”

26

It was sophomore year of high school, and my homie Mike and I had study block and lunch together, which we stayed hype about. One day, in around mid Fall, we were chilling at a table near the back of the cafeteria with a freshman, who was a young black dude. After some time, a young white dude rolled up to say what’s up to him and decided to sit down with us and start talking about this comic that he was writing. He starts talking through the plot and began to flagrantly use “nigger” throughout his description. The young black boy was laughing and I was becoming visibly frustrated, as he seemed to be enjoying the reactions. And I don’t know if it was Jesus, or not wanting anything to get between me and wrestling season, but I held back every desire within me to launch my fists across that table. He finished his story, chuckled, and he left.

27

In college there was a girl that I became interested in for a season. I was anxious for all the reasons any guy would be with becoming interested in someone, but also because, with her being white, the question would always run in my mind of what her family would think of a black man dating her. One winter evening we were hanging out and talking for a while and she told me that a concern for her, if we ever dated, was that her parents didn’t like black people. She said her Dad worked in an industry for a long time where he believed he saw negative stereotypes confirmed and from there became racist towards black people.

28

In fifth grade, I was one of very few black kids in my elementary school. It was the end of one day of class and all of us were getting ready to leave our portable classroom and head to our buses. One of my friends in class, who was a white boy, and I must’ve got into an argument because there was tension between us. As he was walking out to leave, from across the classroom, he said to me, “You’re just a stupid black kid.” Regrettably, overcome with emotion, I sprinted across the classroom, jumped in the air, grabbed his head and slammed it on the top of the nearest desk. He bounced back up, laughed, and walked out of the classroom.

30

In 2017, in Raleigh, one of my close friends came in town with a friend of his that I had never met (both of these guys are white). We got together at a local coffee shop and spent a few hours chopping it up. After a while, the conversation landed on local rappers in the area that my friend’s friend was from. He began looking for a track that an acquaintance of his had created. Without hesitation my friend’s friend said, “Yeah, it’s called ‘Bitch Niggas.’” I was taken back, and he continued to say the title numerous times.

31

A few years ago I was hanging out with a friend who is a white man. At some point in the conversation, the topic of interracial dating came into play. I asked him what his parents would think if he brought a black woman home. Without hesitation he said, “Oh, they’d be pissed.” I responded, “That’s racism.” He retorted, “But they’d get over it quickly,” and I responded, “That’s still racism.”

32

It was last year, Philando Castile and Alton Sterling had both just been murdered by police officers in their respective states and I could not sleep at all. All I could think was that my skin is not a threat. The insomnia led to the creation of a self-portrait that said those exact words, painted on my skin. I posted it on social media with a caption that simply read “#blacklivesmatter.” Minutes later, a comment appeared on the Facebook post from a person who’d been on staff at a church I once attended. It was ignorant, so I deleted it because I was tired–and heavy hearted. The next day this message arrived in my inbox: "Looks like you took down my post on your photo....wow, so if you post something you will only accept positive comments? I’m surprised Trevor. Fact of the matter many people are afraid of blacks. Justified and of course not justified. There are reasons as you well know. Nice photo as I said, but pretty sad, I'm taken back as apparently you support the BLM movement. An organization born out of violence and discord as well as a desire to kill police. Now I know some in the BLM have recently been peaceful in their protest and maybe they are turning a corner for good and positive steps. Not sure just yet, time will tell.”

33

About a year and a half ago, I had brought forth conversations through an article concerning a white PhD’s study upon the idea of “white fragility” into my social media spaces. In that time, I received a message in my inbox from a white man who’d been on staff at a church I was once a part of. He sent me an article attempting to discredit the statement “Black Lives Matter” with faulty evidence that we’d discussed at length before and that I gave numerous resources for. I expressed to him that it was becoming clearer that he had no intention to hear my perspective and then gave him evidence to discredit the skewed evidence, after saying I had no intention to respond after once again giving the critique I had given before. His response was as follows: “Yah we disagree for sure. I hear you Treavor. Read every word. And see a young man who is caught up in past sin of others. Your not hurt by anyone but make your own hurt. You can chose your future as a person who has his being in Jesus. In this world you have trouble. But Jesus overcame the world...As a young person you would do well to listen more and just maybe you don't have the answers for what's going on either. But please do not fool yourself brother. The next black person to die is only 14 hours away. By the way that death will be by another black person. So much for your myth…”

36

It was 2016 after the SuperBowl and Beyonce had performed her song Formation with Black Panther Party inspired costume design. Later that night, I logged onto Facebook and saw a status update by a person in the church I was a part of at the time that was clearly not a fan of Beyonce or the performance, which is fine. As I scrolled down the comments section, I came across a comment from a small group leader in the church, who is a white man, that read, “Her backup dancers' hair looked like poodles,” which the creator of the status liked, who is a white woman. I became very emotional, writing and deleting versions of a comment that said, “You mean afros, like traditional black hairstyle–afros,” & “You might as well have called them bitches.” I ultimately decided that a comment thread was not a place for that debate and remained frustrated the rest of the night. The next day, I was venting my frustration about the comments to a close friend, who was a white man, and he responded, “Well, that must not be what he meant, I know him, he couldn’t have meant that.”

38

It was the weekend of the Charlottesville white supremacist rally. I was in Tennessee hanging out with a few friends from college (who are all white men) at an event and we were laughing and having a really good time. At some point during the night, one of my friends was telling a story that included lyrics of a rap song. Before reciting them, he looked at me and said, “Trev, don’t get mad,” and proceeded to use “nigga” freely.

39

As I sat with a group of white church goers, I mentioned my frustration with the presence of Confederate Flags our area in TN. Two couples sat with me, and one responded somewhere along the lines of, “The flag is about southern heritage, it has nothing to do with racism.” The next person stated that their grandfather fought with the Confederate army and he wasn’t racist, it was just pride for the south and their rights. He said he supported the flag for the same reasons.

41

About 10 months ago, I posted a Facebook status saying, "If someone brutally murdered your grandparents and got off of the charge, and every day, multiple times a day, you saw a public display of their name, how would you feel about that? That's what it's like to be black in the South seeing confederate flags flown proudly everywhere.” A few minutes later, a former high school wrestling teammate of mine sent me this message, which I will only share an excerpt of today: “This is directed at your most recent Facebook post. I figured I would be civil and send you a message instead of commenting. So is that why black people go around killing white people now? Or think that's it okay to destroy this property that's not theirs? To get ‘revenge’ on the whites that lived before their parents were even born? The problem with this statement is that blacks want whites to be less ‘racist’ but continue to be separated by referring to all white peoples as murderers. This is what has to stop!…”

42

I was living in Tennessee at the time and on staff at a church. One Sunday, I’d been on stage to give the announcements and later that week, I was in the office with my supervisor and he told me that someone in the congregation had emailed our pastor about an issue with the t-shirt I wore on stage that week. They essentially asked for him to ban me from wearing it. The shirt was Randi Gloss’ “And Counting” t-shirt (which is pictured) and lists a few well known names of Black men who were killed by the hands of police officers or citizens. My supervisor and I had a discussion about it and I pushed back strongly against the comments of the member of the congregation. He told me we needed to find a balance of me being authentic to myself, but also not being a distraction. I pushed back strongly against that as well and we tabled the conversation for another time.

43

I was at a conference a few years back with some young adults and a couple of pastors I knew then. During that period of my life,I often found myself as the only person of color in the room. It would not be unusual to go days without seeing anyone who wasn’t white. Throughout the trip I was comfortable enough to talk about black cultural norms and try to give those around me a window into part of my heritage and culture. Days after returning from the trip, two white pastors who lead the trip joked among a larger group of pastors and church leaders how they had made a game out of keeping count of how often I referenced myself being black or something relating to it while we were on the trip.

44

When I was 24, I was living in Tennessee, attending seminary and on staff at a church about 30 minutes away in Bristol. Bristol is a NASCAR city and the church was located right around the corner from the racetrack. The fall of my last year in the area, race week hit, and I had a different experience than I’d ever had. Most local people aim to avoid a certain main road to avoid the excessive traffic, but to come from school, I’d need to drive straight through it, so I could get to the office. Because of that, I’d have a daily drive through what felt like a tunnel of Confederate flags, with signs that read, “Heritage not Hate” and merchandise that read things like “The South Will Rise Again.” I remember a deep sense of discomfort, anxiety, and unwelcomeness every time I’d drive through for the few weeks they were stationed on the road. It wasn’t until I came to Raleigh that I fully realized how much of a toll both driving through tunnels like that, or being confronted with Confederate Flags daily was taking on me. I remember the feeling of a weight being lifted and a level of anxiety and stress that I’d grown accustomed to just dissipating. I realized then, more fully than ever before, the violence of that flag’s presence and its history.

45

It was late one evening in college. I had met up with a friend at the time, who was a white woman, to settle a conflict between us. At the end of the end of the night, after talking through everything, she expressed gratitude for the conversation. Standing in the lobby of my dorm, before parting ways, she said, “I’ve really missed this,” then reached out and began running her fingers all through my hair. I was thrown off by it, and was clueless of how to respond, so I awkwardly began running my fingers through her hair as well.

46

It was a late afternoon in the first semester of my final year in college in 2014. It had been a long day of planning, class, wrestling practice, and lifting. I was in the photo studio, setting up for a shoot that I’d have with a classmate, who was a white man, later that evening. When he came in, we struck up some conversation that eventually made its way to the current race issues facing our country. He said to me, “And I really don’t like Black Lives Matter. Why don’t All Lives Matter?” And as I exhaled, I braced myself for the weight this explanation through shallow understanding would place upon me.

47

In my redshirt-senior year of college, I was away at a wrestling tournament with my team and sitting in the bleachers as we waited for our next match. I was sitting with one of our assistant coaches and another teammate who was eating a plate of food. As he was about to start in on the fruit, he looked over at me and joked, “Trevor, do you want a piece of this melon because I know how you people like your watermelon, hahaha.” I shook my head as our assistant coach asked aloud, “Doesn’t that offend you?,” I responded, “Yeah.”

48

In my last year of college, I was sitting in the dining hall eating dinner with some friends and teammates, when another teammate, who was a white man, walked in wearing a tank top that was an all over print Confederate flag. I watched the eyes of all of the Black students in the dining hall widen and watch him as he walked towards the table I was sitting at. As he sat down, I entered a dialogue that was something like this, “Have you considered that you’re offending basically every black person in this dining hall right now?” He responded, “If they want to come do something about it, then let’s go.” I shook my head and responded, “I’m not saying they’re about to do something, I’m saying that your tank top is not considering their experience or our country’s history.” He disregarded the statement and went on to say something about Southern Pride.

49

It was Christmas time in 2015. A live production of The Wiz had just aired on NBC a day or so before, while I was living in Tennessee. I was on a Walmart run with one of my close friends (who was a white man) to buy some Christmas lights and the topic of The Wiz came up. He said something along the lines of, “Why would they produce a show with an all black cast? Especially in this social climate.” I tried to explain that The Wiz is a historically black movie reimagining The Wizard of Oz through a black lens and representing Black people because The Wizard of Oz did not, but it was getting nowhere. He argued that making a production like that with an all black cast was not pushing towards unity and would only create further division. I continued to try and explain the ideas of both representation and paying homage to those who’ve come before you, but he stood firmly in his stance.

50

It was about a year and a half ago, I had gone to lunch with a group of pastors and church leaders. We were all sitting at a table outside of a pizzeria and I asked a close friend of mine, who was a white man, if he’d seen Franklin Graham’s Facebook post from the night before. Graham’s post starts, “Listen up, whites, blacks, Latinos, and everybody else,” before proceeding to explain how to simply avoid a police shooting, followed by a closing remix of the phrase “All Lives Matter” to “every life matters.” We were beginning to discuss how problematic it was when another pastor, who is also a white man, butted into the conversation, defended Graham, and explained to me that the post was simply helpful hints about how to avoid a police shooting. I rebutted about how patronizing and short-sighted Graham’s post was and how it had zero framework of the historical Black American experience, yet he continued to defend Graham with no attempt to hear a different perspective.

51

After moving back to Virginia Beach after a short stinted return to New Jersey, I started 5th Grade at Trantwood Elementary School. After a summer in a new neighborhood, I was one of maybe 3 black kids in my grade and students made sure I knew that. I was into whatever music my brother liked at the time and Christian Hip-Hop was high on his radar. He was very into a group called Cross Movement and in turn, so was I. In class, I talked to the other students about how I liked Hip-Hop and they started to joke me about that. I’ve previously shared an experience where they asked me to dress in Hip-Hop clothes one day just to jeer at me. My memory fails me to remember if it was the same day as that situation, but at some point, one of the boys started calling me “Hip-Hop Donkey,” and the nickname caught on. It wasn’t until a few years ago, reflecting on that time, that I questioned was that a 5th graders’ way of calling me a jackass for my love of my culture?

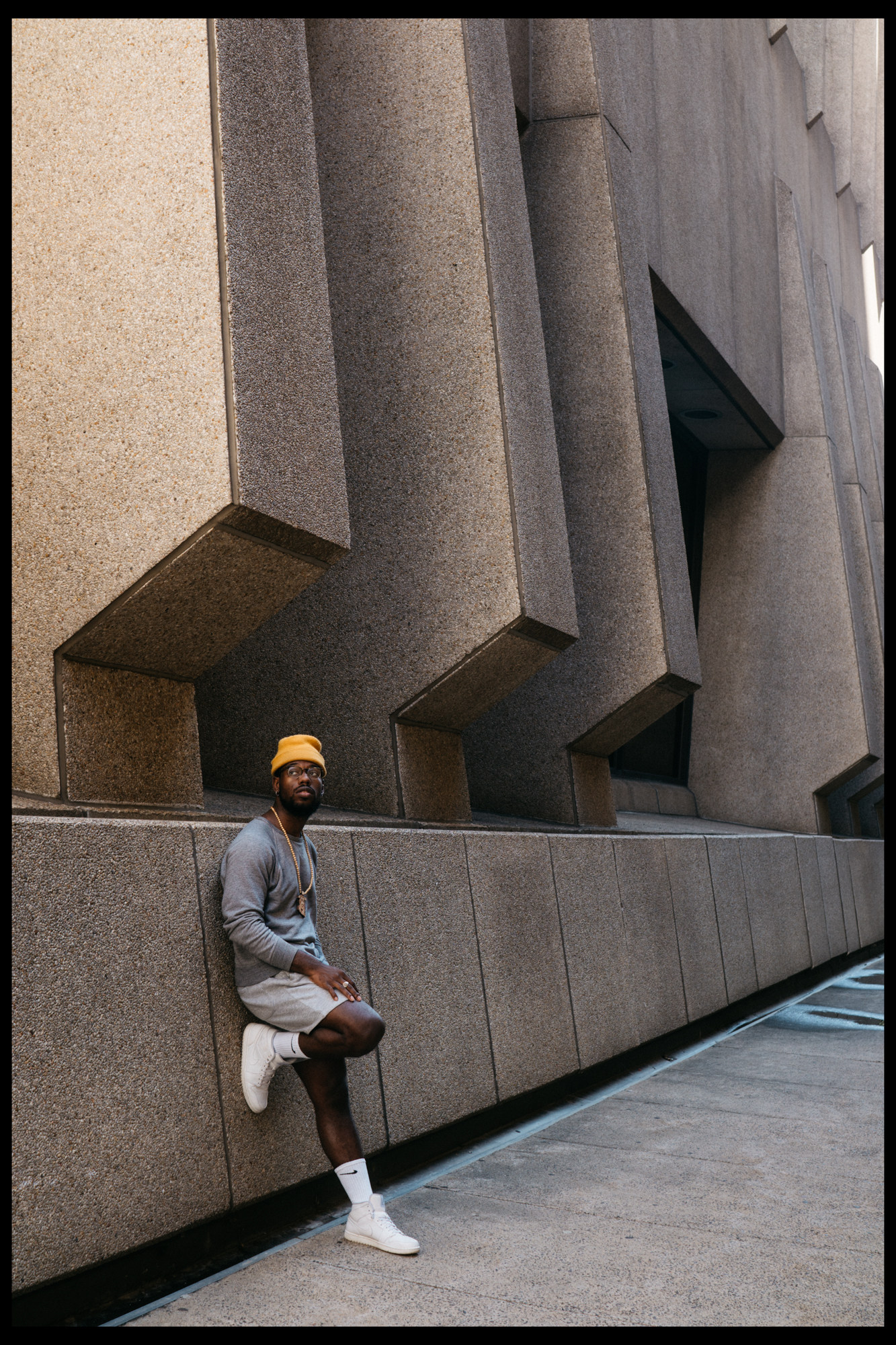

52

It was the weekend of the white supremacists rally in Charlottesville, which was just over 5 months after my move to Raleigh. I’d been in Tennessee to watch a friend’s MMA fight and drove back late to make it to church services the next morning. I’d shot images during the music section of the first service. I couldn’t get cell service inside the lobby, so I decided to head outside and let friends and fam know that I made it back safely. As I was leaning against a wall outside glass doors, a middle aged white woman walked out and said to me, “Can I help you?” Her tone wasn’t welcoming in the slightest, and I’d heard questions voiced this same way in stores I’d been followed around, but gave her the benefit of the doubt. I responded, “Nah, I’m just hanging out.” Again with an increasingly unwelcoming tone, she replied, “Oh, you’re just hanging out, huh?” At that point, I thought, “Why is this happening right now?” It had been a long weekend already and that instance was all too familiar, so I justified my existence in that space in a way that I knew would diffuse the situation instantly: “Well, yeah. I’m on staff here. I’m the new Visual Arts Director.” And instantly her tone shifted to welcoming as she introduced herself then nervously began to fumble over a story about leaving to try and get her son to come to service. She walked away and I stood shaking my head in frustration.

53

In August 2016, while on staff at a church, I was asked by my lead pastor to preach a sermon on Genesis 43 while he was out of town. This is the story of the second journey of Joseph’s brothers to Egypt. I was nearly finished writing when I saw it: verse 32. “They served [Joseph] by himself, the brothers by themselves, and the Egyptians who ate with him by themselves, because Egyptians could not eat with Hebrews, for that is detestable to Egyptians.” It was clear: Joseph, as the 2nd most powerful person in Egypt, segregated the tables at lunch with his brothers and was complicit in Egyptian racism. My pastor taught me to be true to the Text & preach, so I realized that I needed to add to my sermon to do just that. I added a section where I spoke directly to that portion of the story and spoke to the implications of Joseph’s actions. From there, I laid out how this passage can apply to us today by briefly discussing American racism, then broke down the concept of white privilege, without using the term, until I closed with putting the phrase on the project screens and stating, “So when you see this term, that’s what that means.” Sunday came & I preached the sermon. All face-to-face feedback was overwhelmingly positive. However, unbeknownst to me, unrest was stirring elsewhere. I was told (months later) that Sunday evening, at least one elder began receiving many calls of disapproval/frustration about what I’d said. Within the next week, my lead pastor was in a meeting with the leaders from the church planting organization that the church was started through, and within that meeting, they told him that the recording of my sermon needed to come down off of the church website. He responded, “If you have an issue with Trevor’s sermon you need to talk to him about that.” Through the entire situation, I was never spoken to by any of those leaders, nor any of the elders. Although turmoil struck the church shortly after that from unrelated issues, and though it was said to me that the sermon bore no weight on the decision, I remained on staff at that church for another six months and I never preached again. I was the only black person involved in all of this.